DRC: Breaking the silence of survivors

| Gender Links

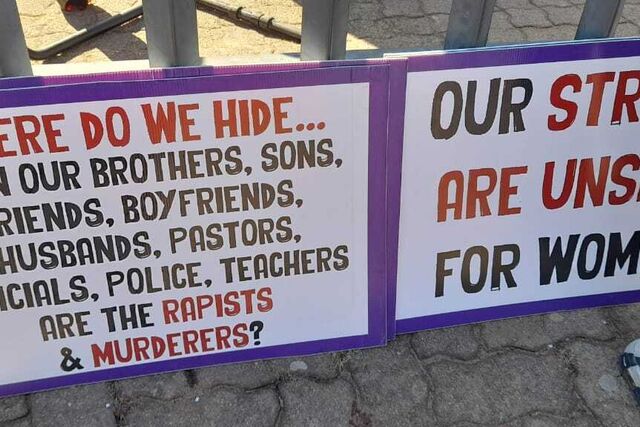

Night was falling over Goma, bringing with it a heavy silence disturbed only by fear. In the streets paved with volcanic stones, the hurried steps of armed men reminded every family that safety was a fragile word, emptied of meaning. This silence, women chose to break. They are not only survivors of sexual violence but also carry the weight of a disability. In their bodies and in their memories, two deep wounds intersect: the one inflicted by armed men, and the one left by exclusion.“When they raped me, I was alone at home and told no one what had happened with two heavily armed men. I was trapped in shame, isolated, until my body began to betray me. Infections were eating me away, and dirty discharge was coming from my vagina. Only then did I find the courage to speak to the neighbourhood chief, who accompanied me to the hospital,” recounts one survivor, her trembling hands gripping a makeshift crutch.During the war and even afterwards, sexual violence struck the women of Goma with terrifying intensity in some neighbourhoods. For those living with a disability, the horror was doubled: their crutches, braces, prosthetics, or wheelchairs were thrown far away by the perpetrators, as if to deprive them of all autonomy. These inhuman acts added to the physical pain a deep humiliation, making recovery even more difficult. In hospitals, medical care was often the only support, while psychosocial and socio-economic assistance remained nonexistent. Most survivors returned home with invisible scars, facing stigma and isolation.Yet some have found the strength to rise. “I thought my voice had no value. But today, I understand that it can change something. Even if others refuse to believe me, I know what I experienced,” says a visually impaired survivor, gripping the arm of a friend who has become her companion.The path to speaking out is long and painful. Some took years to come out of isolation. Shame, prejudice, and fear of rejection even by their families acted like invisible chains. But one by one, they decide to speak. They tell the untellable, they say what so many organisations prefer to ignore. They remind everyone that their disability did not protect their bodies; on the contrary, it made them easy targets.Faced with this imposed silence, the Observatory for the Defense of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (ODDPH) began to act. Mobility aids were distributed to replace those thrown away by the perpetrators, giving women back precious autonomy. In partnership with psychologists, spaces for listening and support were created, allowing survivors to overcome trauma and rebuild their dignity. These initiatives do not solve all problems, but they provide a foundation for survival and resilience.But the action cannot stop there. The solution must be holistic. Survivors need psychosocial reconstruction, economic support, access to adapted services, and above all, social and legal recognition. Programs must include training and employment so that these women can become active agents in their own lives, not passive recipients. Community mobilisation is essential: neighbours, families, NGOs, and authorities must understand that shame and silence are additional weapons used against them.“I was told I had to forget, that no one would want a woman like me. But I refuse to forget. Because if I forget, others will go through the same thing. I speak for myself, but also for those who will never speak,” affirms a survivor, her eyes fixed on the horizon as if searching for a promise of justice in the distance.These voices are stones thrown into the stagnant water of indifference. They call on the Congolese authorities, the international community, UN agencies, and NGOs: human rights cannot be optional, and the exclusion of disabled women survivors is unacceptable. The solution does not rely solely on medical care: it requires the establishment of permanent support networks, education about the rights of persons with disabilities, and active inclusion in feminist and humanitarian programs.Every gesture counts. Replacing a crutch, listening to a testimony, providing psychological follow-up, teaching the community about the importance of dignity and inclusion—these are concrete actions that save lives. Survivors are not asking for favours, but for rights: to walk, to speak, to work, to be heard and recognised as full citizens.Breaking the silence is a weapon. A peaceful but formidable weapon that forces decision-makers to act. In Goma, these women have chosen to speak, to testify, to survive. They prove that life can be reborn after horror, but only if support, resources, and recognition are real.The courage of these women is a call to action for all who have the power to change things. The international community, local authorities, and women’s organisations must understand that disabled women are exposed to particular forms of violence and that their survival requires targeted interventions. It is not just about repairing a body or alleviating pain, but about restoring dignity, returning decision-making power, and offering a future.In Goma, these survivors have decided to break the silence. They will no longer remain isolated. They have shown that even in extreme vulnerability, speaking out and taking action is possible. They remind everyone that survival is not only about staying alive but also about regaining autonomy, respect, and a place in society.The question is simple but urgent: will we continue to look away, or will we finally listen, act, and create an environment where survivors can truly survive and thrive? Their voice, free and strong, can never be ignored again.(*Amani (pseudonym))

Comments

Related news