India: Navigating the digital shift in agriculture

Thinking progress in a digital age

In recent years, the conversation around digitalisation has taken centre stage in India’s policy and development discourse. As digitalisation becomes the default path to progress, one must ask - can a digital future ever be truly inclusive without confronting the historical inequities that have long denied access, voice, and agency to those rendered invisible?

With growing urgency, digitised solutions are being promoted as a panacea to complex agricultural challenges including climate change, market inefficiencies, input management and declining yields. Yet beneath this glossy veneer of digital optimism lies a troubling blind spot: the systemic invisibilisation of women farmers, particularly those who are smallholders, landless, Dalit, Adivasi or otherwise marginalised.

The paradox of progress

The promise of digital agriculture is compelling, but its implementation unfolds within structural realities that remain unchanged. Gender, caste, land ownership, literacy, spatial marginalisation continue to dictate who is seen, who participates, and who reaps the benefits of this digital shift. For many women farmers, especially those without formal land titles, digital access, literacy, or physical mobility, this transformation is not merely out of reach, but is structurally misaligned with their everyday realities.

At the core of this issue is a paradox: women are indispensable to agriculture, yet remain institutionally invisible, unrecognised as ‘farmers’. This absence of formal recognition has cascading consequences, denying them entitlements, visibility in policies, support systems, and a rightful place as program beneficiaries.

There exists a deeply gendered terrain of land ownership, access to finance, education, mobility, and agency. Women constitute a large part of the rural agricultural workforce in the country, yet few own the land they cultivate. This has direct implications on how they are seen by digital agriculture programs. Most schemes, tech-based training, advisories, and precision services are routed through formal registration, mobile connectivity, prior digital literacy, databases like land records or Aadhaar (Government issued identification) linked subsidy platforms, which automatically exclude women farmers from recognition and eligibility. When digital ecosystems are built on datasets that invisible women, they institutionalise inequality and exclusion within the very infrastructure of agricultural reform. As a result, many women farmers are rendered invisible in datasets, and therefore, unintentionally excluded from both policy outreach and digital infrastructure.

Where are the women?

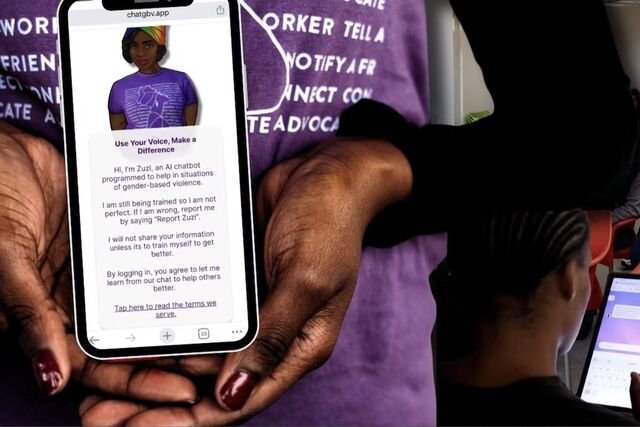

The dormant rhetoric of efficiency and innovation in agri-tech rarely accounts for the real, structural exclusions that define women farmers' lives. Access to smartphones, mobile data, or digital literacy is not a matter of individual motivation but is rather embedded in generational disenfranchisement, patriarchal gatekeeping, and infrastructural neglect. Rural women have often repeatedly articulated that they feel alienated from the wave of digital tools not because they resist technology, but because technology resists them. Trainings are rarely designed for users with limited literacy. The techno-optimist vision is often far from the grounds where women farmers stand.

This disconnect between technological optimism and agrarian realities demands a reimagining of digital agriculture. The next part of the series takes this conversation forward in search of a digital future grounded in justice, equity and recognition.

Rethinking Inclusion - A new digital blueprint

Agriculture is a heterogeneous socio-ecological system, where production is deeply interwoven with caste, gender, and ecological diversity. However, economic formalisation being driven through digitalisation often presumes a standardised subject: the land-owning, literate, mobile-connected male farmer. This narrow archetype systematically excludes the vast majority of women cultivators whose contributions are informal, non-monetised, intergenerational and often collective.

Thus, the limitation, therefore, may not lie in digitalisation per se, but in the techno-economic paradigm it currently advances, one that valorises scale, ownership, and profit without accounting for structural and socio-cultural preconditions that underpin the rural social fabric.

The prevailing momentum behind agricultural digitalisation is dominantly shaped by private capital, platform logics and market rationalities. This alignment privileges scale, standardisation, and data monetisation, often at the expense of contextual agrarian knowledge, context and the sovereignty of producers, particle women farmers. In such a paradigm, the locus of innovation is extractive: geared towards optimising agri-value chains rather than transforming rural livelihoods.

This conversation demands renewed urgency in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). If digitalisation continues to be shaped by gender-blind policy instruments and surface-level inclusion metrics, it will reproduce and entrench the very inequalities that the SDGs aim to dismantle. Even the most robust efforts face structural limitations when digitalisation collides with the political economy of agriculture. The constraint is not merely reach or policy will - it is that the current architecture of digital innovation is epistemologically and economically misaligned with the lived realities of women in agriculture.

A feminist and postcolonial lens demands investment in digital literacy that honours women’s time, aspirations, and diverse learning rhythms. It calls for the decentralisation of control and insists on recognising digitalisation also as a spatial process that is shaped by power, positionality and institutional and social architecture.

To reimagine digital agriculture through a justice-oriented lens is to move beyond pilot projects and isolated success stories. It insists on asking difficult but necessary questions - what models of future are we legitimising when digital innovation is guided by scale, efficiency, and investor interests? Why are certain exclusions normalised? What vision of progress do we endorse when equity and justice is persistently subordinated to efficiency?

Technology holds transformative potential, but only when it is anchored in recognition of those at the farthest margins of power and participation, guided by principles of intersectional inclusion and embedded in the frameworks of structural equity that question dominant paradigms and centre the lived experiences of diverse farming communities. If the digital promise is to be truly inclusive, it must emerge from a different blueprint, which centres justice, equity and participatory governance of technology.

A truly inclusive digital agriculture future demands that investments extend beyond tools to nurturing the social infrastructure of digitality. This includes long-term capacity building, peer-led knowledge networks, community rooted systems of technological engagement, to ensure no one is left behind.

(Written by Charu Joshi, a WOSSO fellow)

Comments

Related news